Launching Substack With a Controversial Take: Film Is More Than Storytelling

As I prepared to write my inaugural Substack post, one question dogged my mind repeatedly: Why am I doing this? Isn't there enough random content congesting the media byways, especially Route A.I.?

But the team at Kino Lorber Media thinks I have something worth committing to print beyond my email screeds. "Keep it personal," they say, inviting me to turn my verbal itches into Substack scratchings. As a former art history teacher and art critic, I entered the film business with a particular perspective, and my team has encouraged me to lean into it…

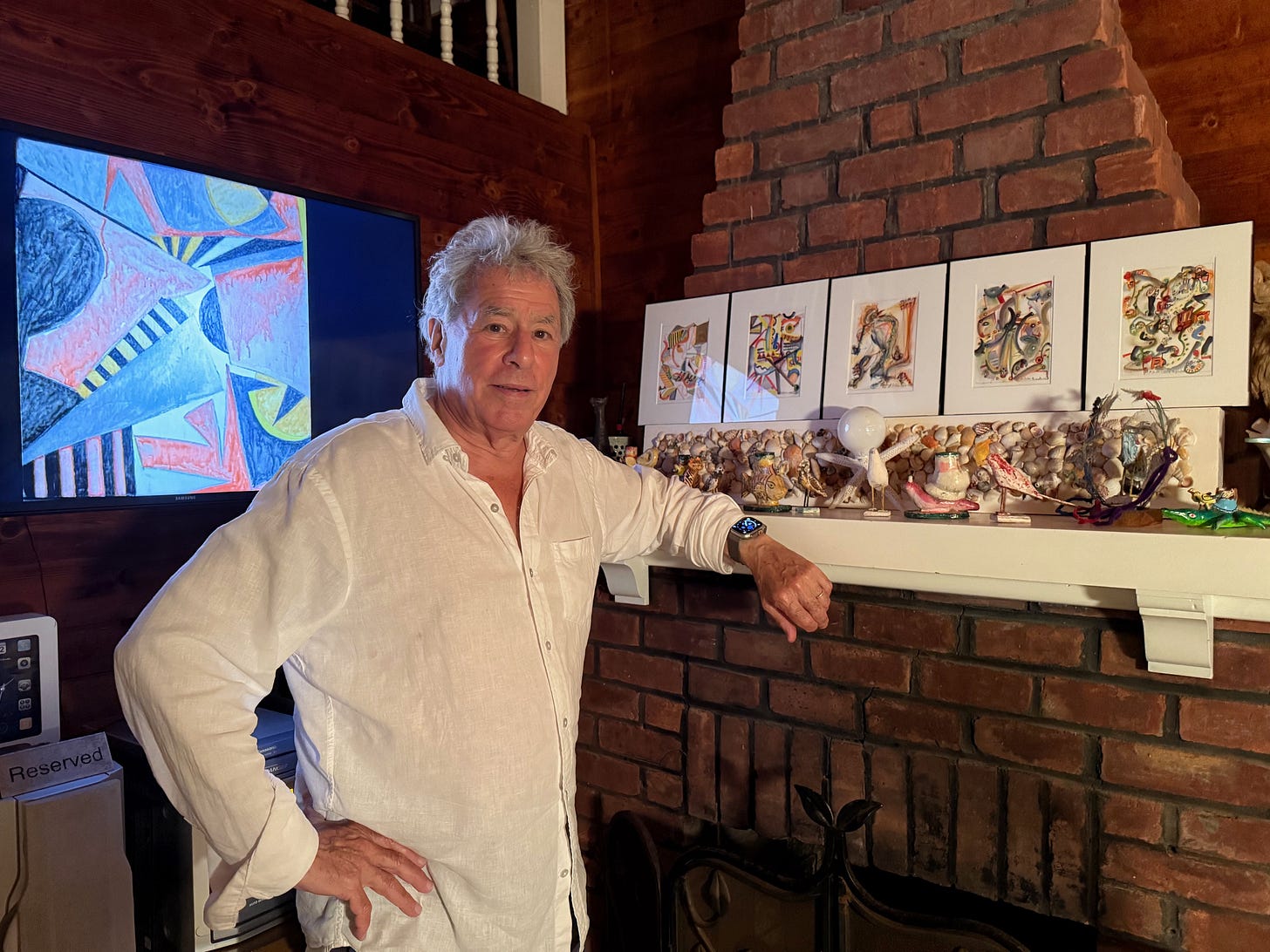

Before starting my first distribution business, Fox Lorber, I spent about a decade teaching art history and related subjects, including as an assistant professor at NYU, while also writing regularly as an art critic for publications like Artforum. Even after 45+ years in film, my engagement with art has only intensified, and today most of my spare time is spent painting abstract compositions with major influences from the Cubists, Constructivists, Surrealists and more recent Abstract Expressionists—I sometimes refer to my work as “cubo-futurist.” Maybe I’ll share a few pieces in these postings from time to time. My painterly immersions are core to how I think about film and the dynamics of this creative process help shape the vision of the businesses I’ve built.

Viewing film through this art lens, I’ve come to a conclusion, albeit a controversial one: Film is so much more than storytelling. Just that term alone—“storytelling”—has a chokehold on the industry. I'm weary of hearing filmmakers and producers at every festival and film event proclaiming their mission as storytellers. Is this literary appropriation really what cinema boils down to? Was that the end game for Méliès and the Lumière brothers at the dawn of the form? My art background might make me biased, but I’ve never believed cinema had less ambition than to be a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. Linear narrative engagement in film—call it “storytelling”—is but one means of giving shape through intellect to the experience of time. If that’s a filmmaker’s main creative objective it risks foregoing the greater non-linear sensory arsenal that can make a cinematic work a truly transformative experience.

The touchstone for this is undoubtedly Jean-Luc Godard. We’re proud to have several of his earlier and most adventurous late works in our collection. Take a look at one of his final films, Goodbye to Language, in our Kino Film Collection. Shot in 3D and aptly titled, the film annihilates the old language of film and creates an entirely new one. And there are others that dare to obliterate filmmaking boundaries too: Yorgos Lanthimos, Guy Maddin, even Bill Morrison’s eye-probing documentaries. These are the types of auteurs that have evolved the medium far beyond the initial concept of “motion pictures” and into “experiential storytelling,” which at least aspires to the sensory expansion of the Gesamtkunstwerk.

But it’s surprising today that linear narrative thinking should still have a purchase on the imagination of filmmakers when everything in our modern media sphere has fractured our experience of time. Between the constant flow of bite-size content on our phones and the cornucopia of a la carte streaming choices on demand, linear storytelling has become a recombinant cubist experience—a mosaic of fragments that flood our senses. Maybe it’s time for our filmmakers to rethink cinema not as storytelling but as a new form that aligns with our new media consciousness.

Stay tuned for more thoughts on film, art, and the art of film.

Film is a visual medium. But structure is still important -- giving viewers something to hang onto.

Thank you for this post, Richard. For my Honours Degree I mastered in Art History and I’m now working on a film. I think it has given me a heightened sense of visual language and potency.

As a screenwriter, I think that storytelling is the beginning of the process, not the end game and if all we give people are the words on our page, then we fail to create an emotional resonance in the audience. It also has to be said, that if we do create an emotional resonance, then it is no longer our story, but it is translated, transformed into a new story, a new cinematic experience in the imagination of those we have inspired to respond. Perhaps the accent at film festivals on storytelling, is maybe due to the fact that they still want to control the narrative?

My dissertation, by the way was ‘The Iconoclastic Disorders of the 16th Century’, which as you can guess, when mentioned at social events, was a real party-stopper; the room would grow silent, I assume with anticipation and baited breath!